In a trade mark infringement case brought by Shorts International Limited (“SIL”) against Google LLC (“Google”) in the High Court of England and Wales, a decision by Michael Tappin KC towards the end of 2024 gave a salutary reminder regarding the scope of trade marks containing descriptive elements.

Anyone who chooses a mark which consists of a descriptive word or phrase and who then registers that in combination with a figurative element should take note.

The infringement action was brought by SIL against the use of “Shorts” in various forms by Google in connection with its YouTube Shorts service. YouTube Shorts is available via the YouTube website and app, and is devoted to playing videos that are less than 60 seconds long.

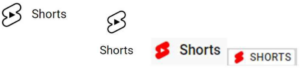

On the YouTube website “Shorts” is used next to an accompanying logo in listings of various “shelves” (such as a “Breaking News” shelf) where videos are grouped. On the YouTube app a creation and upload tool also takes users to a screen in which one of the options is “Short”. SIL complained about use of “YouTube Shorts”, the word “Shorts” alone, and the word alongside the Shorts logo in various manners:

Each of these uses was alleged to infringe SIL’s earlier trade mark registrations under Sections 10(2) and 10(3) of the UK Trade Marks Act 1994, and to amount to passing off. Google denied infringement and further raised a defence under Section 11(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 that its use was of a sign which is not distinctive or is descriptive and was in line with honest practices.

SIL relied on an earlier word mark registration for “SHORTSTV” and various figurative marks which combine the word SHORTS with the symbol of a red triangle within the letter “O” which is reminiscent of a “play” symbol. The following is an example of one of SIL’s figurative marks.

The registrations covered various goods and services in classes 9, 38, 41 and 42. Google’s goods/services were accepted in some respects to be identical to the goods/services of the registrations and the case under Section 10(2) turned on whether the marks were similar and whether there was a likelihood of confusion.

SIL claimed that its marks benefited from a reputation for the purpose of its allegation of infringement under Section 10(3) and that they had sufficient goodwill to establish a claim for passing off.

Google counterclaimed for invalidity of the registrations on grounds of lack of distinctiveness. They alleged that the registered marks consist exclusively of signs that may serve to designate a characteristic of the goods/service or have become customary in the current language. It was also alleged that the older registrations should be partially revoked on grounds of non-use.

A significant point in the case was the meaning of “shorts” at the relevant date. The parties agreed that by 2018 “shorts” was in use to mean “short films” but disagreed as to whether “shorts” was also in use for short-form audiovisual content. The evidence for the relevant period showed that there had been various references to a “short” or “shorts” in the UK press. The judge considered these were sufficient to show that it would have been natural to refer to “YouTube shorts”.

The judge noted, as argued by SIL, that not all short audiovideo content is referred to as “shorts”. However, advertisements and music videos are normally of a short length such that the use of the word “shorts” to refer to these would not be expected.

Having found that “shorts” means short-form video content including but not limited to short films, the judge held that the word “shorts” would be recognised by the average consumer as a description of a characteristic of goods for which the earlier trade marks were registered. The red triangle in the earlier figurative marks would also be recognised as a “play” symbol designating that the goods can be played. However, the way in which these elements were combined in the earlier figurative marks, with the play symbol in red located within the “O”, was sufficient that the combined mark did not consist “exclusively” of indications that may serve in trade to designate a characteristic of goods such as “sound, video and data recordings” or services such as “broadcasting”, “entertainment services” and “production, presentation and distribution of films, videos and television programmes”. The counterclaim for invalidity of the earlier figurative mark registrations therefore failed.

For the earlier mark SHORTSTV, the judge held there is no perceptible difference between this mark and the mere sum of its parts and this registration was held to be invalid for many of the goods and services for which it was registered. It was held there was no evidence that among a significant proportion of the general public this mark had come to identify goods and services as originating from a particular undertaking.

On the case for infringement the outcome was in favour of Google. The judge spent some time considering how to identify the signs being used from the perspective of the average consumer, taking into account the context in which consumers will see the allegedly infringing signs. Google’s position was that save for limited use of “Shorts” on creator pages, it was merely using composite signs in the form “YouTube Shorts”, or “Shorts” in combination with a figurative element. On the YouTube website (but not the app) the YouTube name and logo was always present on the screen. In the app, “Shorts” was used with a logo that was deemed to bear a resemblance to the YouTube logo which would be noticed by consumers.

It was held that the word “Shorts” on the creator pages was being used purely descriptively and not as a trade mark in relation to goods or services.

In the case of the composite marks as they appear on the YouTube website, the judge held the average consumer would understand that the word “Shorts” is being used descriptively but also as part of a composite sign including the logo, which overall operates as a trade mark. The inherent distinctive character of the earlier figurative marks was considered to be low and to come solely from the combination of the word “shorts” and the play symbol in red in the “O”. There were deemed to be some visual similarities in that the respective marks all contain “Shorts”, but there were also visual differences. The aural and conceptual similarities were deemed to be obvious. However, the similarities were at a level which differs from that which gave the earlier figurative marks their distinctive character.

Considering the strongest case on infringement the judge held that the use by Google on the mobile app of “Shorts” with a logo having a play sign, but without the YouTube name or logo appearing on the screen, did not give rise to a likelihood of confusion, given that the particular combination of the word “Shorts” and play symbol in the “O” which gave the earlier mark its distinctive character was absent from the alleged infringement. The case for trade mark infringement under Section 10(2) failed.

If the SHORTSTV mark had been held to be valid for relevant goods and services the judge would have held its distinctive character arose from the combination of “Shorts” and “TV” which is absent from all of Google’s signs.

SIL’s marks were held not to have a reputation in the UK for the purposes of Section 10(3). The judge went on to say that if a reputation had been found to exist for short films then on balance they thought Google’s marks would bring to mind “short films”, YouTube and SIL’s marks. However, this would not dilute the distinctive character of SIL’s marks which arises from the combination of “Shorts” and the play symbol and it would not be demeaning for SIL to be associated with YouTube Shorts.

The judge went on to say that had there been a finding of infringement, the Section 11(2)(b) defence would have failed on the basis that Google was deemed to know about SIL’s objections, and if SIL’s allegations had proved to be correct, then Google could not properly be regarded as acting fairly with regard to SIL’s interests. The passing off case failed at least on the basis that Google’s use of “shorts” did not amount to a misrepresentation or cause damage to goodwill.

This case serves as a reminder that where a mark has a low distinctive character (at least where that has not been enhanced through use), a likelihood of confusion with an allegedly infringing mark may not be found to exist even where there are significant similarities concerning aspects of the marks which are descriptive, if there are insufficient similarities in those aspects which give the earlier mark its (low) distinctive character.